CHARLESTON LANDMARKS

Lighthouse Landmarks

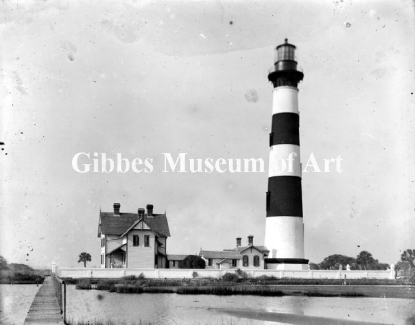

There are two historic lighthouses on barrier islands flanking the mouth of Charleston harbor. The Morris Island tower dates to 1876, and has stood against the ravages of time and nature to become one of the most famous lighthouses on the Atlantic coast. The Sullivan's Island light, built in 1962, was once the most powerful beacon in the Western Hemisphere, and is still in service, seen clearly 26 miles at sea.

Charleston's first true lighthouse was built on Morris Island in 1767. Designed by Samuel Cardy, whose other towering triumph included the 186-foot steeple of St. Michael's Episcopal Church, the 42-foot tubular brick construction featured a burning lamp of whale oil or lard. Strengthened and heightened during remodeling in 1802, the light served the city until a more powerful, revolving beacon extended aid to navigation from a new 102-foot tower in 1838.

The second Morris Island lighthouse was an easy target in the midst of what became a major battlefield during the War Between the States, and was completely destroyed. It wasn't until the end of Reconstruction that a 161-foot brick tower was again raised on Morris Island, withstanding severe hurricanes, a major earthquake, occasional water spouts, and even a few near-misses during World War II bombing exercises.

The eventual decommissioning of the Morris Island lighthouse came not as much from obsolescence as from erosion, which, ironically, was more influenced by mankind than by nature. In 1878, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of separate stone jetties - one starting on Sullivan's Island and the other from Morris Island - that would extend 14,000 feet almost completely submerged to flank the harbor channel. Built by sinking log mattresses loaded with stone, the jetties were intended to funnel the flow of ebbing tide along the channel to scour the bottom and maintain depth. Modern hydrologists have found that, along with channel silt, the jetties have been responsible for washing away a huge chunk of Morris Island.

The Sullivan's Island lighthouse was commissioned in 1962. Anchored by steel girders on a concrete foundation, the 163-foot tower was built of aluminum paneling in a triangular pattern to withstand the most severe hurricanes. Its original candlepower capacity was so intense that it was feared the lighthouse could temporarily blind mariners, and was reduced to 1,170,000 candlepower in 1967 - still strong enough to be seen far beyond the limits of American territorial waters.

Even though Sullivan's Island would boast the first American lighthouse to feature an elevator and air-conditioning, the beacon could not stem a turning tide of global positioning technology that reduced the need for visual references, and would be the last of its kind built in the United States. Fully automated in 1982, the light on Sullivan's Island is still in service.

Harbor Forts

As Fort Sumter neared completion in 1858, it was considered an engineering marvel and a source of pride to Charlestonians, who took ferry excursions past the three-tiered fortress standing fifty feet above high water. Less than a decade later, it was a charred pile of rubble less than half that height, but would never lose its luster in the eyes of succeeding generations of visitors. Construction of the pentagon-shaped fort began in 1829, but was delayed by disputed claims on the small spit of sand overlooking the harbor entrance where foundations were erected from 70,000 tons of New England granite and rocks, and was still unfinished when he local federal garrison barricaded themselves inside and eventually draw the 1861 attack that led to Civil War. The relatively unscathed fortress seized by Confederates would be subjected to one of the longest continuous sieges in the history of warfare, bombarded by Union fleets and batteries with more than seven million pounds of projectiles in the course of 20 months, as defenders carved caves from the debris.

The fort was used by the U.S. Lighthouse Service until 1898, and was remodeled and re-garrisoned for the Spanish American War before the last blast came during anti-aircraft practice in World War II.

Castle Pinckney�s original design was almost impressive as that of Fort Sumter, conceived in 1808 as a twin-tiered, elliptical fortress. But the plan never materialized and the little fort never earned much respect. Its location on the inner harbor soon became obsolete, as the only shots ever fired were military salutes during garrison duty until 1832. The fort was used at the beginning of the Civil War as a lock-up for Union prisoners from New York, who festooned cell barracks with signs that read �Hotel de Zoave� and Musical Hall 444 Broadway.�

Serving only briefly as a harbor channel light at the turn of the 20th century, Castle Pinckney suffered further indignity by being removed from the National Monument list in 1951, and today sits covered in weed and sinking in mud, as crowds pass by on boats to Fort Sumter.

West Point Mill

Today, the four-story Classic Revival mill building is obscured by heavily-trafficked bridge approaches, clusters of modern buildings, parking lots, and rows of yachts, but once it stood alone as one of the city�s most industrious endeavors.

West Point was a small sliver of land protruding into the Ashley River in the 1830�s, when a steam-driven rice mill was built and powered by water from large areas of man-made pond. An 1859 fire destroyed the mill, which was replaced one year later with a structure that housed giant boilers and massive cylindrical shafts for grinding and brushing kernels into polished rice and flour. The 15-acre complex included separate shipping wharves, carpenters� sheds and cooperage facilities, as well as new artesian wells for water supply.

For more than half a century, the West Point mill was among America�s largest and most productive, annually cranking out hundreds of thousands of barrels, and when a foundering rice business finally forced the facility to close in 1926, much of the oversized inventory was bought by Henry Ford for display at his Edison Institute antique museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

In the late 1930�s, remnants of the old mill ponds were dredged for a municipal yacht basin and planned as the site of a transatlantic seaplane terminal in an agreement made by the city with the German Air Ministry, but the coming of World War II shot the project down.

The abandoned building remains Charleston�s only completely intact rice mill, and has been used for Chamber of Commerce headquarters, a restaurant and city marina offices, and the old mill pond area now supports high-rise condominiums and hotels, and approaches to Ashley River bridges, where the watery foundation is still evident in an undulating roadway surface.

Call or Email Today to Reserve Your Tour - 843-433-9324 | footprints1670@gmail.com

|